Doug Robinson

Robinson articulates the disconnected nature of our every day. Consistent with post modern practices in the photographic arts, Robinson is guided by the discipline of deconstructing the strictures of both representationalism and formalism.

Always aware of the larger historical lineage out of which painting has emerged, Robinson's works are systematically governed by a strength of line and classical techniques used in the ordering and manipulation of perception. Both cerebrally and viscerally his work stands as an important contribution to the world of contemporary visual arts.

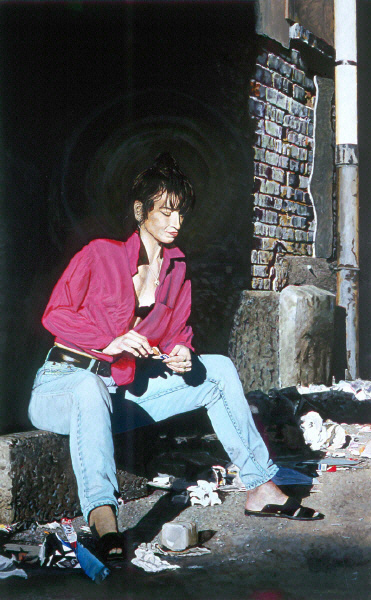

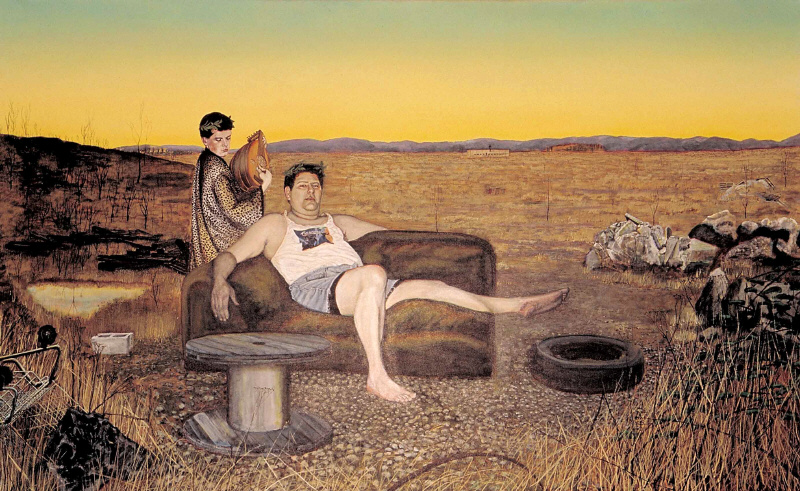

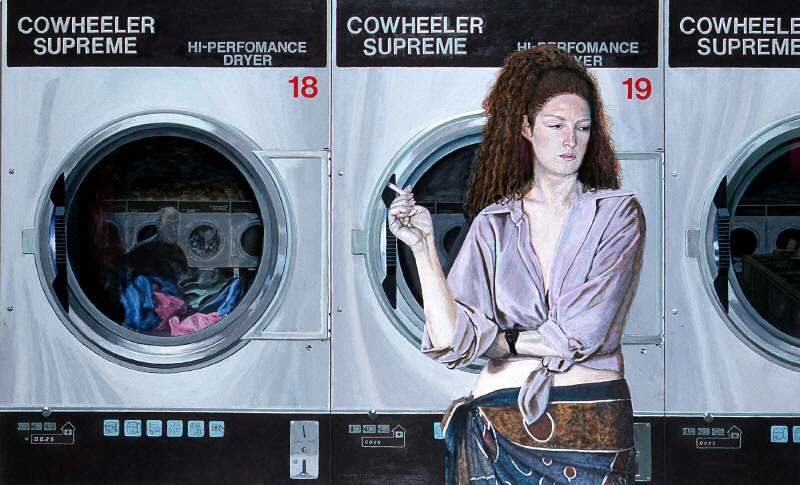

Cowheeler Supreme

48 in x 77.5 in

acrylic on linen

Exhibited at Artropolis 2001, and the B.C.Festival of the Arts, Robinson’s “Cowheeler Supreme”

is a wryly conceived portrait of a young woman smoking in a launderette amidst big steel machines. Pictorially it is reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s scene of existential alienation in “New York Movie” (1939). The woman’s gaze, while markedly contemplative, is textured with both sadness and the sense

of being dislocated. Through her somber demeanor, Robinson effectively infects the picture with a sense of gloom and depression. Closer reading discloses that his composition is not so unified, and not so serious-toned; rather, the portrait is a cheeky staging of melancholy. The strong geometrical units of the shiny metal dryers both frame the subject and are a subject. They occupy a separate mathematical spectrum on the canvas. In opposition to the spiral that engenders the pose of the female subject, they are governed by the proportional construct known as the “golden section”. Superficially, by standing as a metaphor for an oppressive apparatus, the dryers underscore the young woman’s mood. However, by the force of their size and gloss, they compete with the human subject and register as another foreground. Robinson’s trick is to make the so called fore and aft elements appear integrated even though, relatively, they are detached from one another.

A further destructuring of the portrait takes place in mirrored irony. To the woman’s right in the glass window of the upright dryer unit is the muted reflection of the painter who, in this self rendering, bares a striking resemblance to Sigmund Freud. The site of this mischievous figure also breaks the mood we have previously attributed to the woman. She is apparently not alone or lonely

in her despair. The scene is a folly; Robinson’s composition announces itself as contrived.